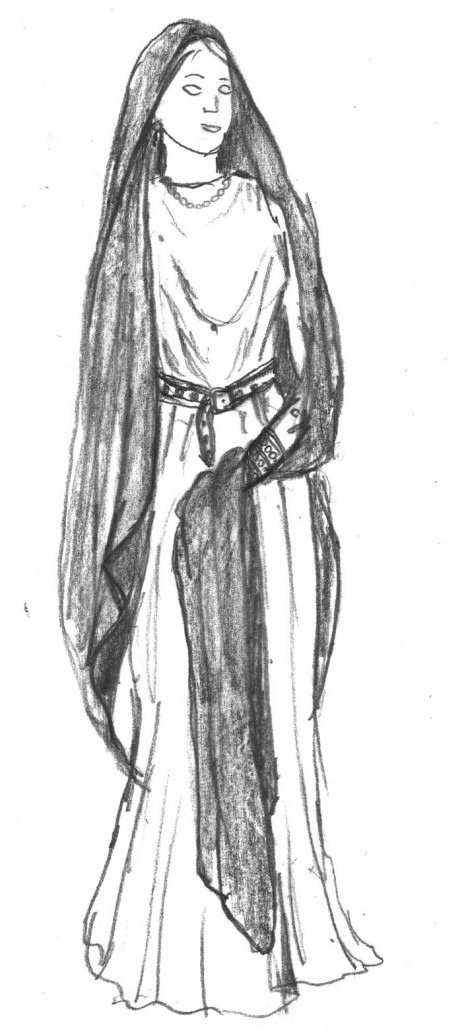

The women‘s status

The woman is officially her husband‘s subject. Her place in society is traditionally at home, whereas the man has to be publicly active. From the moment of birth a woman has to accept her father as her warden, who will give her into her husband’s custody through marriage. That‘s the law. Reality naturally is a horse of a different color. Although it is hard for women to exert influence publicly, many of them find their ways of doing so by shaping their father‘s, husband‘s (or lover‘s) opinions and actions.

In general, married women are well-respected. They are valued guests at banquets and feasts, and are allowed to visit the theatre, the arena and the public bath. They also have the possibility to engage in arts and science, and are thus able to attain high levels of education.

It is forbidden for women to join the military service at the legions, and they are not permitted to hold a political position.

One of the rare opportunities for a woman to gain direct public influence is as a priestess, as some religious duties may only be peformed by women.

When it comes to crafts, some works were regarded as feminine – such as doing laundry, weaving, spinning (or the fabrication of clothes in general) –, while others – like cooking, pottery and art – were executed by both genders.

Women who deliberately ignore those social standards are deemed to be especially scandalous and dangerous.

The family

The family is the main pillar of roman society and represents it’s own little microcosm embedded into the public cosmos of the city. The head of the family is the pater familias, the father. He governs his wife, sons, his daughters, his grandchildren, his slaves, his clients and the family-fortune. While he is still alive, the prospect of inheriting his wealth is his most powerful instrument for keeping the family committed to him. Only after his death will his sons truly be free men, finally empowered to take control of their own lives and their heritage. If the pater familias dies before his daughters are married, a tutor (most likely some close kin) will take responsibility for their lives until a husband takes over the wardship.

A widow is free from wardship (if her father is dead, of course) and may shape her life according to her wishes.

The patronage

The patronage is a complex system of dependences within the roman society. Clients are dependent on their patrons, and owe them their loyalty and support, but in return profit from their patron‘s support and influence. Many common citizens are clients to influential decuriones (members of the city council), or to gang-bosses. In doing so they add to their parton’s authority, but in turn are also able to count on their support – for example during a lawsuit.

Foreigners always need a roman patron to be allowed to act officially within the city walls, for example when doing trade or signing contracts.

Clients pay their respect to their patrons every morning by visiting him and offering their services to him for the day. If one has his own clients, one will receive them before that, taking them to one‘s own patron afterwards, if necessary. The payed respect will often be rewarded with a small present or a small amount of money.

The supreme patron of all romans is the emperor.

The social stratums

One is born into a social stratum, but one does not have to die in it. Almost everyone within roman society may climb up or fall down the social ladder.

The aristocracy (patricii)

The roman upper-class are called patricians (from patres – fathers). Frequently thinned out in ongoing civil wars, emperors usually fill up these ranks with trusted families. Often sovereigns of conquered regions, now loyal to the roman empire, were ennobled to this rank. Patricians still allocate the social elite of the empire and posses great power and funds. Some priestly offices are confined to patricians only.

In case of conviction after a lost lawsuit – provided he or she isn‘t able to pay the fee for freedom – the patrician is not threatened by death-penalty, as commons civilians would be, but only by exile. High treason being the exception to that rule. Traditionally, aristocrats draw their wealth exclusively from land ownership, agrarian economy, soil resources and the spoils of war. To practice a „common“ craft or trade is, for the patricians, not only objectionable, but utterly unthinkable and associated with a loss of honor.

The money nobility (equites)

The rank of equites once emerged from the civilians who were rich enough to buy a horse (equus) for war. By now the rank of equites has no relation to war anymore. To hold this rank one has to account for and demonstrate a certain wealth. As an eques, one enjoys the benefits of fortune without the constraints and responsibilities of the patricians.

Families of equites or patricians who once brought forth a consul are counted among the rank of nobilitas – those famous families who bear the highest ranking politicians of the empire.

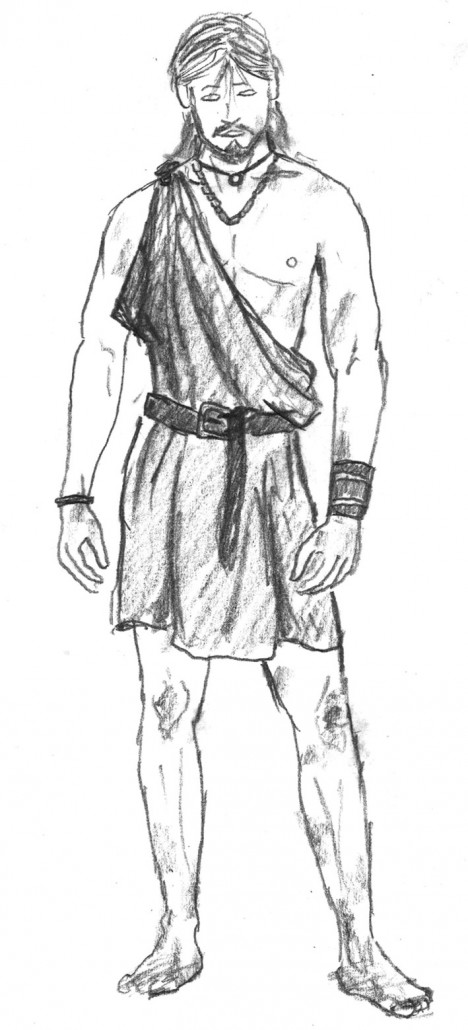

The commons (cives)

Farmers, Craftsmen and Traders who are able to provide (ideally) not only for themselves, but also for their families, and who sometimes even have a slave. They are the backbone of the empire. Not the possessions of the rich, but the crafts and trades of the commons secure the survival of the state in times when no profitable wars are waged.

The plebs (plebes)

The lower class, mostly uneducated and dependent on casual labour. Some work as day labourers or do other menial jobs, but by doing so they have to compete directly with the much cheaper slaves. Others terrorize the neighborhood, wandering the streets in gangs (collegia), all too often headed by especially brutal or canny men and women with great power.

To keep the plebs calm, emperors regularly host games (ludi) and donate grain, without which many plebs wouldn‘t even survive (panem et circensis). The power of the ruthless gang-bosses, who recruit their thugs from the plebs, is based on that poverty.

The freedmen and freedwomen (liberti)

Freedmen and freedwomen are former slaves who were freed by their masters. Due to the patronage-system they are usually still dependent on their former masters, in whose name they often hold important positions. Freedmen and freedwomen may not participate in politics (they are not allowed to hold a political position). However, their children or at lastest their grandchildren will be accepted as full-fledged roman citizens. Especially former slaves who once belonged to the state (the emperor) often work in influential positions as freedmen, for example in financial services.

Slaves (servi)

Slaves are unfree. They are owned by a person (the dominus or the domina), by a community or even by the state itself. They do menial work in quarries, corpse-pits, on fields, in households, as caretakers, teachers or cooks – or, on the other hand, they act as treasurers or secretaries of important politicians. They are the foundation of the roman culture.

By law a slave is not more than cattle. The only right a slave possesses is the right to work. Slaves may not go to court, and as witnesses they are only allowed to give testimony when tortured. Slaves are at the mercy of their masters, (causeless) cruelties against slaves however are regarded as crude and are seen as a sign of the owner‘s bad character. When a slave (or a foreigner) is executed, they often will be crucified or sent to the arena for the purpose of deterrence. Nevertheless, slaves may sometimes own small possessions and may even be able to fight for their freedom in front of the law, as long as they can prove that they were unlawfully enslaved.

Some slaves are freed by their masters when they get old, and some may even buy their freedom. A gladiator may, after many victories, receive the symbolic wooden sword (the rudis) as a sign of their freedom. Many slaves wear plates of wood, metal, leather or clay around their neck, on which the names of their masters are noted.

Foreigners (peregrini)

The foreigners are free people to the empire, who are not provided with civil rights. Most of them are foreign traders or immigrants who were not born within the borders of the empire. To be able to work and trade it‘s necessary for peregrini to find a roman patron.