Roman cult practices are similar to magic rituals: If the rules and formulas are followed exactly and without faults, the gods are compelled to be benevolent. For this reason, rituals are an integral part of nearly all aspects of daily life . This strict adherence to traditional rites is a particular quirk of Roman religion, and results in a vast abundance of rules and limitations in all aspects of the cult. Even the smallest deviation from the way the rites are meant to be performed forces their repetition, lest the wrath of the gods should be invoked.

The divinatio, the interpretation of signs from the gods, is also very important. The intentions of the gods are usually clarified according to a very convoluted system of rules by a number of seers who work on behalf of the state. These experts include Augurs, who observe lightning bolts and the flight of birds, and Haruspices, who read intestines.

In Scarbantia, the temple at the forum is the principal place Romans use for public religious expression. It is dedicated to Iuppiter (Optimus Maximus), Iuno and Minerva, and is based on the famous temple on Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Religion is also practiced at home, either at the hearth or at a small domestic shrine. Here they will make small, non-bloody sacrifices – such as incense – to the genius or iuno (the individual ‘creator spirit’ of every Roman), the lares (house- and travel spirits) and the penates (house- and storage supply spirits). The responsibility to carry out these rites falls to the head of the house. Romans believe that spirits and demons are about and active everywhere, and it is common to believe in magic.

Imperial Cult

One particularity of Roman culture is the cult surrounding the emperor. People make sacrifices to dead and living emperors alike.. Although their likenesses are worshiped, they are not seen as gods (deus), but rather as god-like (divus). The living emperor also has the function of pontifex maximus, and is thus responsible to bring salvation to the Roman state.

Taking part in religious ceremonies, revering the gods and the emperor and eating the sacrificial meat are integral parts of a life as a good Roman citizen. Anyone who avoids these ceremonies is regarded as highly dubious, and is actively threatening the pax deorum – the peace with the gods, and the common good.

In the provinces, worshipping the emperor is seen as a statement of loyalty towards Rome. This is a problem especially for christians, as their first commandment forbids them to worship gods other than their own.

| Iuppiter | father of gods, lightning, thunder, air |

| Iuno | family, marriage, birth and poverty |

| Minerva | wisdom, science, strategy |

| Neptun | sea, earthquakes, horses |

| Mars | destructive war, battles |

| Venus | love, beauty, sensual desire |

Christianity

First scarcely noticed by the Romans, the ideas of this former Jewish sect are growing in popularity among the lower social classes of the empire. In contrast to the imperial religion, Christianity promises salvation and absolution, both of which are attractive new concepts to the impoverished plebs.

Many christians say they are praying for the welfare of the state and the emperor, and therefore claim to be true to the Roman Empire. However, the difference between praying for the emperor and praying to him is significant in this case, as it implies a renunciation of the imperial cult. Moreover, they are preaching their doctrine of refusing to give the imperial symbols their due in full-throated missionary activities. This threatens to drive a wedge into the Roman social order, which has led to bloody local prosecution.

“For this reason the christians are enemies of the state, because they refuse to give the emperors their senseless, dishonest and overbold tributes; because they, as humans who possess the true religion, will celebrate the emperor’s holidays with their hearts rather than with excesses.” – Tertullian

We know from Pliny the Younger that the Roman state does not systematically search for christians. However, people who are reported as christians are given the choice to either bring a sacrifice to the emperor (i.e. to renounce christianity), or to be executed. The result is a situation of permanent insecurity for christians, which makes them dependent on the benevolence of non-christian neighbors.

Mystic Cults

These cults underline the magical character of Roman religion. They exist alongside the imperial cult, and should be viewed as a supplement rather than an opposition. Those who have been inaugurated in the mystic cults may continue to participate in the state cults, which is why even emperors have been known to be part of them.

Most commonly known is the exclusively male Mithras cult, introduced by legionnaires from the east. Outsiders do not know much about the Mithras cult, as initiates are forbidden to speak about it. The mytrhaeum in Scarbantia is inaccessible to the uninitiated. The seven levels of ordination are open to all participating men, including slaves, regardless of their social status

Women also have an exclusive secret cult, called Bona Dea, which men are excluded from. Only married women may take part in Bona Dea celebrations, and just like their male counterparts, they are not allowed to talk about what transpires at these gatherings.. The rituals take place in private homes, most of the time those of magistrates. Male slaves and animals are also forbidden, and even statues or pictures of men are covered. Attempts of men to disguise themselves as women in order to take part in these celebrations is considered sacrilegious, and is punishable by death.

Divination

Romans who want to find out about small or personal things, who want to ask about the future or talk to the deceased,turn to a soothsayer. They can be found in colourful tents at the forum, where they offer their services when they are not busy being chased out of town. Female soothsayers are particularly well regarded, and are known as saga. Their evil counterpart would be the malefici, a witch, but the differentiation between the two can be tricky.

| Aesculapius | medicine |

| Apollo | Grannus | poetry and healing |

| Bacchus | wine, intoxication and intemperance |

| Bona Dea | fertility, virginity |

| Ceres | soil, fertility, harvest |

| Fortuna | luck, coincidence |

| Furien | goddesses of revenge |

| Isis | queen of the sky, rebirth |

| Merkur | thieves, trade, travellers |

| Nemesis | to give what is due |

| Pluto | lord of the underworld |

| Serapis | protection, serves as a universal deity |

| Vesta | hearth fire, family union |

| Victoria | victory |

| Vulcanus | volcanos, fire, smiths |

Death Cult

In Roman society, the grief over the loss of a loved one goes hand in hand with a pronounced fear the dead, which is of course tied closely to the belief that life continues after death, even if there is no universal afterlife. Whether one believes life after death continues on an island of bliss (elysium) or one is doomed to a bleak, shadowy existence (hades), it is common to assume that the dead can influence the fates of the living. As a consequence, it is considered important to remember the ancestors in order to keep them from haunting your home as lemures.

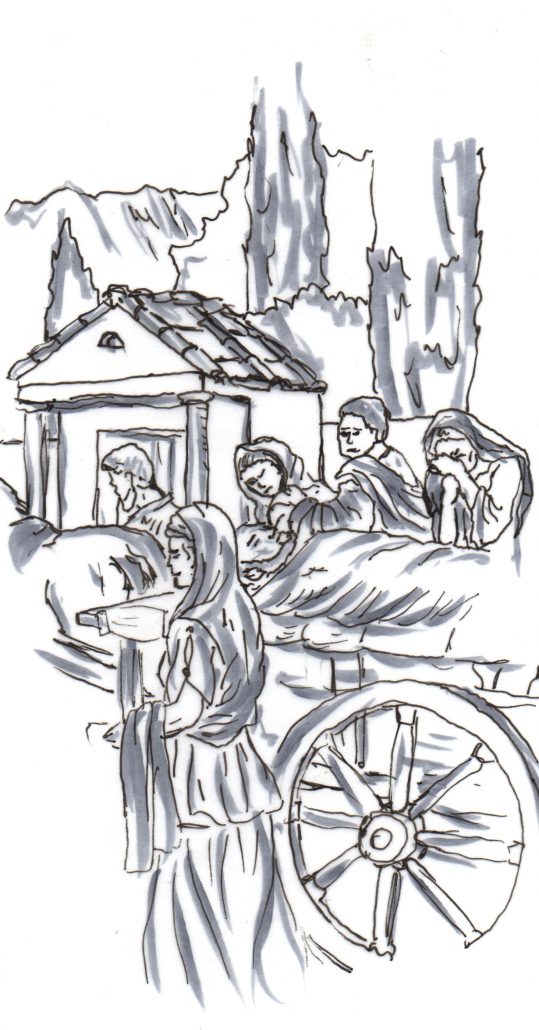

In the face of imminent death, relatives and friends will assemble at the bedside of the dying person to say goodbye and offer comfort. The closest relative will give the dying person a kiss at the moment of death to catch the soul escaping the body, and will then proceed to close the eyes of the deceased. Everyone present will call the deceased by name, mourn him or her, apply ointments, dress the body and put a coin under the corpse’s tongue to pay the ferryman for the journey into the land of the dead.

The body is carried by relatives – or former slaves which were freed to mark the occasion of their former master’s passing – in a funeral procession accompanied by mourners. This procession leads to the family graves or catacombes, which will be located outside of the city. The funeral is followed by a meal, after which any relatives have to undergo a purification ceremony involving fire and water.

Important days of remembrance are birthdays (dies natalis), and the anniversaries of the deaths (festi dies anniversaarii) of family members. On these days, relatives and friends light some lamps and hold a meal at the grave of the deceased person, who is meant to derive some sense of comfort from these ceremonies in the afterlife.