Munus | Munera

The funeral games, originally intended to honour the dead by pitting gladiators against each other, have long since turned into spectacular mass events for public amusement. Emperor Augustus declared the sacred tradition an imperial privilege, which is why nowadays gladiator fights may only be hosted in honour of the emperor.

Gladiators, most commonly slaves and prisoners of war, face each other in predetermined pairs. Usually, a referee (lanista) will decide the victor, but public voting in tight situations is not unheard-of. It’s either “mitte!” (let him go!) or “iugula!” (stab him!), but gladiators rarely receive a death sentence, as they are valued professionals. It’s a different story with criminals, however, who are to be executed in the arena (damnatio ad gladium/ferrum) and have little hope of survival. Usually, these public executions take place before the actual main event, the gladiator fights.

Gladiators receive their soldier-like training in the well-guarded ludus (gladiator school). Some schools (familia) will also travel from city to city, renting their gladiators to anyone willing to host such games (in honour of the emperor, of course).

Romans maintain an ambivalent attitude towards gladiators: On one hand, they occupy an even lower rank in the social hierarchy than slaves, but successful gladiators may achieve great fame, exemplifying Roman virtues such as courage and defiance of death. Cicero and Seneca regarded a gladiator calmly accepting his fate as an exemplum virtutis – an example of manly virtue.

Some gladiators can amass a rather loyal following among the female citizens. In this context, the well-known term gladius (ram sword) gains a rather vulgar secondary meaning.

Finally, gladiators are also battle-hardened combat veterans with little to lose. Ever since Spartacus and his slave revolt, the Romans have become rather vigilant in controlling this dangerous lot.

Comedy | Tragedy

Theatre plays are very popular as well, especially if they are bawdy and/or particularly sentimental.

Roman comedies are usually non-political, and features simple narratives and characters. They serve to amuse the public, but may also contain criticism of perceived social injustice.

Tragedies, on the contrary, are more complex and, like their Greek antetype, tell a portentous story of the bitter fate of a protagonist stuck in hopeless situations. According to Aristotle, tragedy aims to cause a change of heart with their audience, achieving catharsis by making them live through emotions such as misery and terror.

A band of actors, referred to as grex, is commonly led and managed by the dominus gregis, the director. Especially tragedies may also feature an additional choir, vocally expanding on the plot. Actors will often wear flamboyant masks as an additional means of conveying emotions.

Casual games

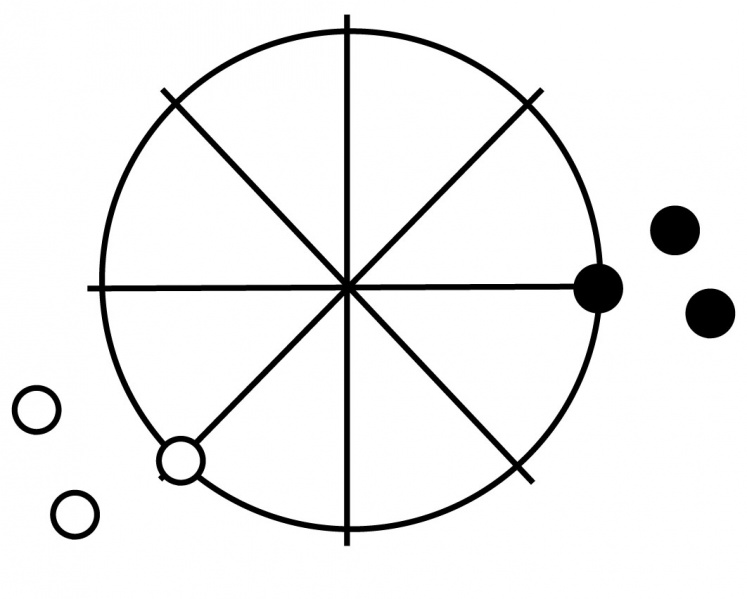

Mola Rotunda

Round Morris is a game for two players, each getting three stones of different colours.

A circle is split into eight equal segments, resulting in nine points of intersection (eight on the circle, one in the middle).

To begin with the three stones are placed along the first row on the edge of the circle, leaving one row free in the middle.

Players then take turns moving one of their stones, but they may only move from one free intersection to the next. Aim of the game is to create a straight line through the central intersection with all three stones.n.

Canis

For 4 to 10 players, three dice are needed.

Each player puts the agreed-upon stake on the table. Players may then roll the three dice three times in a row before giving them to the next player. If they roll a 1, they need to put that die aside before rolling again. If someone accumulates three 1s during his three attempts, he’s out and has to throw his stake into the pot. Last man standing wins the pot.